Mission Matters #51 – Robert L. Frey: Use of Intellect as Economic Historian & Steward of Religious Heritage

This academic year we are reflecting on the student experience of different generations of alumni and current students.

This month’s Mission Matters focuses on the life and work of an alumnus from the Class of 1960. In Part One (MM#50), I focused on Robert Frey’s reflections about his student years. In this second part, I discuss the significance of Frey’s professional work as a historian and the role of inquiry and the synthesis of knowledge throughout his lifetime (especially during retirement) for how we think of the mission of the University of Indianapolis. A third part (MM#52) will explore Frey’s reflections about what we can learn from history, especially with respect to the struggle in the United Methodist Church, with which the University of Indianapolis has been affiliated since 1968.

By Michael G. Cartwright, Vice President for University Mission and Associate Professor of Philosophy & Religion, based on autobiographical reflections of Robert Frey, Ph.D. ’60 and the published obituary, used with permission of his daughter Ms. Brenda Frey Kraner, Ph.D.

One of the most subtle features of the mission of the University – our own, or that of any institution of higher education – is how the curriculum encourages students, faculty, and staff to wrestle with the vicissitudes of human history. Many things change – including the mission statement of the university! Our current mission statement does not have an explicit “outcome” that specifies what students must learn with respect to history. This creates tension. Some faculty and staff lament this state of affairs. Others approve. And the ongoing argument is integral to our mission. Indeed, you might even say it is a feature of our intellectual heritage.

I would argue, however, that it is almost impossible to imagine how UIndy students can develop critical sensibilities for serious inquiry without developing a capacity for historical thinking. Indeed, the earliest origins of the notion of “inquiry” coincide with exploration about the past. (The word Herodotus used to convey that concept was “historia” – in case you don’t read Greek). What the UIndy mission statement does have is a robust statement about the importance of enabling students to learn to “use the intellect in the process of discovery and the synthesis of knowledge.”

In different respects, the craft of history and the quest for heritage involve both. Robert Frey ’60 is an example of a UIndy alumnus who, I believe, managed to engage in both pursuits without ignoring the differences and without presuming that they were mutually exclusive. In this second piece about Frey’s life and work, I want to lift up Frey’s remarkable contributions in the context of exploring some of the tensions between history and heritage in American society in our time.

Robert L. Frey, Ph.D. – Historian, Teacher & Administrator

I met Robert L. Frey in the late 1990s shortly before he retired as Dean of the University of Charleston (WV). Beginning in 2000, he enjoyed spending more time with his wife, daughter, and four grandchildren. As his obituary reports, Bob also began to explore “the history of the Evangelical United Brethren Church and served for many years on the Advisory Council for the EUB Heritage Center at United Theological Seminary and edited its publication, Telescope-Messenger.” For a few years, he even taught courses in American Religious History at United Theological Seminary, where his father George had once taught.

I met Robert L. Frey in the late 1990s shortly before he retired as Dean of the University of Charleston (WV). Beginning in 2000, he enjoyed spending more time with his wife, daughter, and four grandchildren. As his obituary reports, Bob also began to explore “the history of the Evangelical United Brethren Church and served for many years on the Advisory Council for the EUB Heritage Center at United Theological Seminary and edited its publication, Telescope-Messenger.” For a few years, he even taught courses in American Religious History at United Theological Seminary, where his father George had once taught.

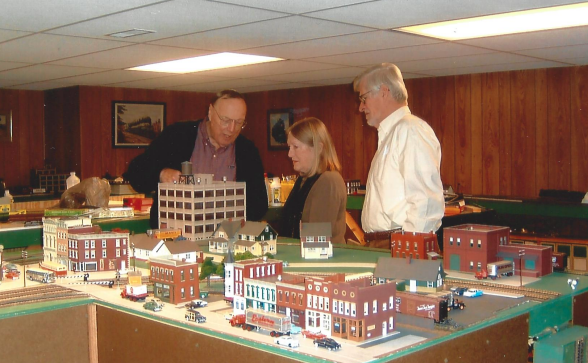

When I first read Bob’s obituary (1938-2018) this past summer, I paused to chuckle over the whimsical description of his attire: “Always known for coming to church in a coat and tie, he was a throwback to an earlier era something in which he took a certain amount of pride as a historian should.” Come to think of it, I don’t think I ever saw Robert Frey in any other mode of dress (see the photograph above). But then, I never saw Bob in the basement of his home where he could often be found exploring his lifelong love of model trains and railroad memorabilia. (Nor do I think I know enough about what hobby meant to him to be able to connect that interest with his academic roles and professional interests.)

Although Frey was an academic historian, teacher, and administrator, I think readers would be incorrect to conclude that Frey was formal and standoffish. I don’t recall ever being present when he introduced himself with a title. He was simply “Bob” – a warm, effusive fellow, who was eager to engage in conversation and much of the time also ready to listen to others. In these respects, his life was lived very much in the present tense. Make no mistake about it though. This man had a life-long passion for railroads, he loved his alma mater “ICC” (or UIndy), and he cherished the legacy of the Evangelical United Brethren Church. And in all three arenas, he was a steward of the heritage that he shared with others.

Having already shared excerpts of Bob Frey’s memoir about the student experience (see MM#50), I want to introduce readers to his life-work across six decades. The published obituary summarized his academic career:

“He earned a Master of Arts degree from Pennsylvania State University (1962) and a Doctor of Philosophy degree in economic history from the University of Minnesota (1970). Over a 40-year career in college teaching and administration, he taught history at Penn State, Shenandoah University (VA), University of Minnesota, and Lynchburg College (VA), as well as a few courses for United Theological Seminary (OH). He was the Dean of Wilmington College (OH) and Vice President for Academic Life at the University of Charleston (WV). In these positions, his strengths were curriculum development, faculty governance, and ensuring academic success.”

In addition to his work as a teacher and administrator, Frey was a very active scholar. Here again, his obituary provides the basic facts: “During Robert’s professional career he authored, co-authored, or edited eight books, numerous articles, and made many presentations to a variety of groups. His major interest was in railroads, and he co-authored a five-volume history of the Northern Pacific Railroad and its locomotives.” To cite but one representative work, Frey edited Encyclopedia of American Business History and Biography, Railroads in the Nineteenth Century (1988).

Although I have done little more than dip into Frey’s scholarship, his contributions are striking for the ways that he offered a detailed analysis of successive technological developments (steam, coal-burning, compound, etc.) in railroad transportation. He also published articles in heritage periodicals such as The Bulletin of the National Railway Historical Society, the readership of which included “rail-fans” and retired railway employees, as well as academic historians like him and his peers. Frey’s focus on a single regional railroad (The Northern Pacific) helped clarify why often even the best efforts to make the railroads efficient were unsuccessful.

Railroads in American Cultural History – Emerging Amnesia

Most of Bob Frey’s contributions as an economic historian of railroad transportation were published well before cultural historians began to study the effects of railroads on other aspects of American folkways.

About the same time that Bob retired, Stephen Ambrose published his widely appreciated narrative history Nothing Like it in the World (2000) about “the men who built the transcontinental railroad” between 1863 and 1869. Ambrose’s book shows how the advent of the transcontinental railroad changed the way that Americans thought about human history and their own place in it. Consider for example one of the earliest dramatic observations of this kind (1889): “The world of to-day differs from that of Napoleon more than his world differed from that of Julius Caesar, and this change has chiefly been made by railways.” (Ambrose, 25) To the extent that such perspectives became popularized, Americans found themselves thinking about their place in human history in new ways.

I can imagine Bob reading Ambrose’s narrative history as soon as it was available. My guess is that he read it with great appreciation – as many railroad fans have also enjoyed it – but I doubt that Frey learned much new from Ambrose’s fine book. Bob would not have been oblivious to the ways in which the American heritage of railroads is entangled in complicated patterns of memory and nostalgia. The fact that railroads are examples of disruptive change is something Bob knew before most of the rest of us.

None of these recent developments would have surprised Robert Frey Ph.D. For those of us who have not spent our lives studying the economic history of railroads, there are ways to catch up. Here is one provocative example. In his wide-ranging book Mystic Chords of Memory: The Transformation of Tradition in American Culture, Michael Kammen tracks the transformation of the railroad in American cultural history:

“During a span of roughly a century and a half, the railroad shifted from being a symbol of dramatic and unimagined progress (the 1830s and 1840s) to representing abusive and regressive economic power (1880s and 1890s) to becoming the object of wistful nostalgia on the part of tradition-oriented train buffs. . . . From dangerous cinder sparks to embers of sentiment: the railroad really exemplified Hawthorne’s notion that progress is circular rather than linear. Here we have an instance of transformation: from innovation to tradition via memory, in about five generations.” (48)

Because American remembrance of the railroad is not uniform, to some extent these patterns of memory overlap with one another, and to the degree to which nostalgia is operative, our memories of the past become distorted and even false. Kammen argues that this is a characteristic feature of our culture as Americans: “American culture contains a dualistic tension where myths are concerned. We can be iconoclastic, but we are much more likely to be permissive and self-indulgent about myth.” (26)

Kammen explores the problem of American amnesia as a function of “the American inclination to depoliticize the past in order to minimize memories (and causes) of conflict.” (701) Over and over again, in the face of ongoing social conflicts about economic power that continue to exist in American culture, we remember a past that never was because it is too painful to confront the challenges of the present. This denial of the conflicted present, Kammen argues, leaves Americans vulnerable to an almost incorrigible nostalgia about our past.

Kammen’s argument about the extensive nature of American amnesia about the past notwithstanding, we do not have to give up hope that our attempts to incorporate our knowledge about the past are always myopic. To do so is to give in to cynicism, something that I don’t think that Bob Frey ever did. What it does mean, however, is that it requires uncommon self-discipline to avoid misreading the significance of whatever “heritage” we embrace. I think Bob Frey is a great example of how one can exercise attentive reception of heritage without becoming obsessive. Before I explain why that is the case, I need to describe a related trend that pertains both to Kammen’s thesis and the life-work of Robert Frey.

The Emergence of the Heritage Craze in American Life

If Americans display a tendency toward amnesia about the past, there is also plenty of evidence that some Americans have an obsessive desire to preserve the past. Consider the oft-told joke about participants in the heritage craze of our time: “How many preservationists does it take to screw in a light bulb?” The correct answer is said to be four: “One to change the bulb, one to document the event, and two to lament the passing of the old bulb.” Concern for preservation holds the potential for good and ill alike. On the one hand, “The current craze for heritage . . . offers a rationale for self-respecting stewardships of all we hold dear; on the other, it signals an eclipse of reason and a regression into embattled tribalism.” So says David Lowenthal, whose elegantly written book The Heritage Crusade and The Spoils of History (2001), describes the twentieth-century origins of this widespread development.

As some preservationist efforts have generated controversy, the tension between “history” and “heritage” has become almost palpable. Lowenthal chastens those who refuse the distinction between history and heritage and is no less trenchant in reminding readers that there is no way to eliminate the overlap between these two forms of knowledge synthesis. “No aspect of heritage is wholly devoid of historical reality; no historian’s view is wholly free of heritage bias. . . . just as yesterday’s heritage becomes today’s history, so we, in turn, embrace as heritage what our precursors took as history. . . .Yet history too is a heritage. The history we normally accept without demur stems from seldom-tested faith in the cumulative probity of historians, even when we know their chronicles were forged . . . in the crucible of self-interest.” (The Heritage Crusade, x-xi)

Not all heritage advocates are belligerent in their dispositions about how to interpret the past, to be sure. Within the broader company of those who act upon their strong sense of stewardship, there are people who have a sense of humor about the ways in which the desire to preserve the past can sometimes lead to ridiculous lengths. Bob was not ashamed to call himself a “rail-fan” any more than he apologized about wearing a suit and tie to church on Sunday mornings. I can imagine Bob’s laughter as he nodded in response to the joke about preservationists’ efforts to replace a light bulb as he recalled some of his own experiences across the years with fellow “rail-fans.” At the same time, he shared the concern about the eclipse of the railroad in a culture marked by struggles to build and sustain a nation-wide transportation infrastructure that serves the greater good of society while preserving personal autonomy (often symbolized by the automobile).

Bob Frey’s Stewardship of the Heritage of the EUB Church

My guess is that Bob also knew some United Methodists whose dedication to the preservation of the heritage of the Evangelical United Brethren Church could be no less obsessive. What such examples have in common, of course, is the experience of loss and the anxieties that cultural change brings about. Bob often talked about the ways that persons who had been raised in the Evangelical United Brethren Church experienced a sense of dislocation as a result of the 1968 merger with the Methodist Church to form the United Methodist Church (UMC). Those who had been raised in the EUB Church had a strong sense of pride in the denomination’s witness to ecumenism as well as in a long history of leadership founded in a strong sense of warm-hearted piety and a disposition to agree to disagree about topics (such as “infant baptism” vs. “believers’ baptism”) that had proved to be very divisive in other sectors of American Protestant Christianity.

Shortly after the merger that formed the UMC, a group of formerly EUB leaders founded The Center for the Study of Evangelical United Brethren History in 1978. For the next 12 years, participants in the work of the Center focused on conservation and collection of papers and holding meetings at which they could share memorabilia and research. By 1989, members of the Advisory Board for the Center . . . “making the tradition available for the present and future stimulation of the church.” The leaders of the History Center established a newsletter for that purpose.

Interestingly, the Advisory Board also candidly stated a bias that they brought to the work of the Center. “We believe that persons are more important to history than institutions and would like to identify important persons and their contributions” (emphasis mine). Over the next decade, the Center carried out an oral history project, established an endowment to support the work of the center, and sponsored a conference or two that invited scholars to explore the church’s heritage.

But the primary vehicle for promoting the work of the center was a newsletter that appeared three times a year. The Telescope-Messenger took its name from the two periodicals – The Religious Telescope and The Evangelical Messenger – that had contributed so much to the growth and development of the two religious denominations that had come together to form the Evangelical United Brethren Church.

Robert Frey was not one of the founders of the Center for the Evangelical United Brethren Heritage. Nor was he a member at the time that the new focus was implemented. The initial editors of the Telescope-Messenger newsletter were a pair of faculty colleagues from United Theological Seminary, men of the same generation as Bob’s father Prof. George Frey. Although the difference in age between Frey and his predecessors was not vast – something that he noted in his initial editorial — Bob also understood that nevertheless, he represented a new generation taking on the responsibilities of this center for collecting and developing the heritage of the EUB Church. Because Bob’s predecessors were both clergy, his status as a United Methodist layperson also marked an evolution in the cultivation and stewardship of the EUB heritage in addition to the professional credentials that he brought to this volunteer role.

Bob’s 19-year tenure as the editor of Telescope-Messenger coincided with a significant shift in the exploration of the EUB heritage. As he indicated in his first issue (Jan. 2000), his goal was to capture “personal anecdotes, stories of local churches, conferences, events, programs, reminiscences, biographies or autobiographies . . .” Bob Frey went out of his way to work with members of this association for the preservation of the EUB heritage. For example, the first issue that Bob edited featured an article by Bishop Paul Milhouse (ICC class of 1929) entitled “My religious heritage.” But sooner or later careful readers of the newsletter would discern that Bob Frey also was attentive to institutional entities, including the colleges and universities – like his alma mater UIndy – that were associated with the EUB Church.

Bob was an opportunity-oriented steward of EUB Church heritage resources, and there were times in recent years when that benefited the university. Although he wrote extensively about his college days (see MM#50), I don’t think Frey made a fetish of his student experience at Indiana Central. Nor was he guilty, in my judgment, of engaging in the kind of “crusade” about the heritage that was tribalistic in nature. Bob did not merely receive submissions. He also solicited articles from scholars, and on occasion, he also took the time to write pieces that explored controversies of past and present (for an example of the latter see MM #52).

Frey’s Stewardship of the Heritage of his Alma Mater

Bob’s work as the editor of the Telescope-Messenger also provided him with opportunities to reflect on and contribute to the intellectual heritage of his alma mater. I want to point out three instances of this that I think should be more widely known.

First, Bob could be counted on to participate in historical projects and activities that celebrated the university’s religious heritage. Memorably, he served on the planning committee for the November 1, 2016, All Saints Day Symposium at which we celebrated the Evangelical United Brethren Heritage, an event that was co-hosted by the University of Indianapolis and University Heights UMC. I consulted him on several articles that I wrote in the past two decades. Invariably, he identified trustworthy sources (for even the most obscure queries), and I could always count on him to catch mistakes that resulted either from misconstruing examples or overgeneralizing based on the weight of the evidence. We occasionally disagreed about how to account for the odd facts of EUB history, but in all cases, Bob was both congenial and astute.

Second, more than anyone else I know, Bob Frey has contributed to the way I and other UIndy historians and interpreters understand the University’s heritage. For example, in 2013, Frey wrote an article for the Telescope- Messenger about his memories of ICC in which he juxtaposed the campus that he had known with the campus that Paul Milhouse had encountered in the fall of 1929 (based on a description that Milhouse had written many years before).

“The campus I encountered in the fall of 1956 was strikingly similar to the campus Paul and Francis [Noblitt] Milhouse saw in the fall of 1929. After a flurry of construction in the 1920s, it was many years before the campus saw a major new building. In fact, the only buildings on the campus in 1956 not there in 1929 were the World War II surplus Quonset huts that served as married student housing. During the first semester of my freshman year, ground was broken for what is now Esch Hall, the new administration-library classroom building. Before I graduated a new gymnasium (finally) was also constructed. But the University of Indianapolis campus of 2013 would be essentially unrecognizable to either Paul Milhouse or to me had we not seen it since our graduation.”

I am struck between the similarity between this observation and the aforementioned perspective cited by Stephen Ambrose about dramatic perceptions of the landscape of the past that resulted from the construction of the transcontinental railroad between 1863 and 1869.

Bob Frey certainly brought a lifetime of experience as an academic historian to his post-retirement activities on behalf of the Center for the Evangelical United Brethren Heritage, but as this reflection from 2013 indicates, he was also trying to understand himself in the context of the wider landscape. In doing so, I don’t think he was guilty of being overly dramatic. On the contrary, he was taking the measure of new knowledge, and thereby enabling the synthesis of knowledge to proceed to engage newly opened possibilities.

This past year I shared Bob’s observation about changes in the campus landscape “between then and now” with a group of alumni that Andy Kocher and I had brought together to help us think about the Campus Heritage Maps project that our colleague Randi Frye had recently completed. I asked the group whether they thought that Bob’s observation was accurate. In response, an alumna who had graduated a couple of years before Bob described feeling disconcerted when she first learned that Ransburg Auditorium would be the new location for commencement.

Amy Buskirk Zent ’58 recalls that she understood that it was a privilege “for the Class of ’58 to be the first class” to use the new facilities, but she also had looked forward to participating in the longstanding “tradition” of holding graduation on the lawn of Good Hall. By the time Bob Frey graduated in 1960, Ransburg Auditorium was where everyone expected graduation to take place. It was part of a new set of expectations that saw the center of campus on the North side of Hanna Avenue in the Academic Building (now Esch Hall).

One test of the value of any effort to share and/or synthesize knowledge is whether it engenders more knowledge sharing. This is one instance where Bob Frey’s work did that.

This leads me to the last of the three examples that I want faculty, staff, and alumni of the University of Indianapolis to know about. Shortly after the publication of Prof. Frederick D. Hill’s centennial history of the University of Indianapolis, ‘Downright Devotion to the Cause’ (2002) Bob arranged for an excerpt from the book to be published in the Center for the EUB Heritage’s newsletter, the Telescope-Messenger.

As I recall, Frey had initially planned to write a review of his former professor’s book, whom he had admired for more than 40 years, but he ultimately decided not to do so. I know that he corresponded with Fred Hill about the book and I think it is likely that Bob questioned some of Dr. Hill’s judgments. He also recognized that Hill’s book was a labor of love and not well-suited to an audience of persons whose interest was more in the EUB heritage than in institutional history as such.

I am not sure how much Frey edited the material (which is essentially a collation of paragraphs taken from the beginning and end of the 401-page book). I do know Frey tried to produce a text that gave readers of the Telescope-Messenger a sense for the institutional culture of the University. He never made any negative comments about Downright Devotion to the Cause, but the collation that he put together (based on paragraphs from the beginning and end of the book) has turned out to be a very useful resource for Bob’s alma mater’s own institutional purposes. “The Legacy of Education for Service” (published under Frederick Hill’s name) has been used in New Student Experience classes for more than a decade as a way of interpreting the University’s heritage of “Education for Service.”

Heritage, Mission, and the Synthesis of Knowledge

I know many faculty, staff, and alumni who are fierce advocates of the importance of making sure that — in the future as in the past and present — the University of Indianapolis continues to enable students to learn to “use the intellect in the process of discovery and the synthesis of knowledge.” I share their pride in that aspect of our intellectual heritage. I also think Robert Frey is one very important exemplar of this feature of the university’s mission. And I hope that one effect of writing this article is that more people will take pride in the achievements of alumni like Bob.

I hasten to add, however, that we should not make the mistake of acting as if the University is singularly responsible for the excellence of Bob’s life and work. That would be as critical a mistake as permitting our minds to be clouded by amnesia about the past or an uncritical disposition toward preservation of the past. At the same time, I think UIndy faculty and staff could benefit from understanding some of the factors that may have played a role in Bob Frey becoming such an adept interpreter of the heritage that he valued enough to steward. That is a conversation that I leave to others except to observe that he was an “insider-outsider” figure.

Bob had enough insider knowledge about the EUB Church and Indiana Central College to be able to appreciate things from an institutional perspective. Having been raised in Eastern Pennsylvania, Bob felt like an outsider as an ICC student in the 1950s. Because he did not resonate with Hoosier folkways and/or Midwestern sensibilities, he struggled to conform to expectations of his peers. As the son of a professor-clergyman, he knew more than most students about the official leadership of the EUB Church in the 1950s, but as a former member of the Evangelical Church (prior to the merger that formed the EUB Church), he could understand how minority students like George Gobah (from the EUB mission field in Sierra Leone) felt at ICC.

Quite possibly, Bob had some of these insider-outsider instincts before he ever set foot on the ICC campus in 1956. His years of graduate study as a historian developed his skills, which he put to work in the service of the church and the academy alike. And then, there is his work as an academic dean, where he worked with faculty and administrators alike to shape policies and programs that served the common good. Finally, Bob was well-educated enough to be able to be able to engage United Methodist clergy, but as a layperson, he could see things from a non-professional perspective.

No one can see all sides in the present moment – unless perhaps we are talking about the kind of overview that someone who builds model train landscapes might aspire to have. That is the kind of exception that proves the rule. We don’t have omniscient knowledge of ourselves and the world around us much less do we have the capacity to synthesize all that might be known about the past. Some of the questions we ask are the product of heritage and the more we know about history, the more likely we are to confront the limits of our questions.

Let us not forget that our collective interest in the past also has limits. Bob Frey was certainly aware of the fact that interest in the EUB heritage was fading, and that divisions within the United Methodist Church were one of the contributing factors. As his 80th birthday drew near, Bob confided (to me among others) that he wasn’t sure there would be anyone who would step forward to edit the Telescope-Messenger when he was no longer there to do it. That is a sad fact of life for any historian to confront, much less one disposed to be a steward of a well-loved religious heritage. At the same time, he was a forward-looking person, and he went about his various pursuits with a good sense of humor and a hopeful demeanor.

These are but a few of the things I think UIndy readers should know about Bob Frey ‘60 in order to put the picture of “the man who always wore a coat and tie” into perspective alongside the images of him as a model railroad hobbyist, an academic historian, and proud steward of his religious heritage as a United Methodist layperson who was the son and grandson of Evangelical United Brethren and Evangelical Church pastors.

*****************

The last part of my Mission Matters reflection about Robert Frey’s life work (MM#52) discusses one of the final articles he wrote for the Telescope-Messenger, which consists of a reflection about “What History Teaches” which he wrote (as a layperson) in the context of the preparations for the United Methodist Church’s 2019 General Conference. As always, I invite your feedback at missionmatters@uindy.edu. In the meantime, thanks for taking the time to reflect with me.

Remember: UIndy’s mission matters!